Community in Crisis Pt 1: What A Dog Mayor Says About Politics

Small Towns, Big Ideas, and (Re)Building Community in 2020

Thanks for reading the Frame Strategy newsletter, in which I explore how individuals and companies can find lessons out of this year’s challenges to create a better world. Sign up for more here.

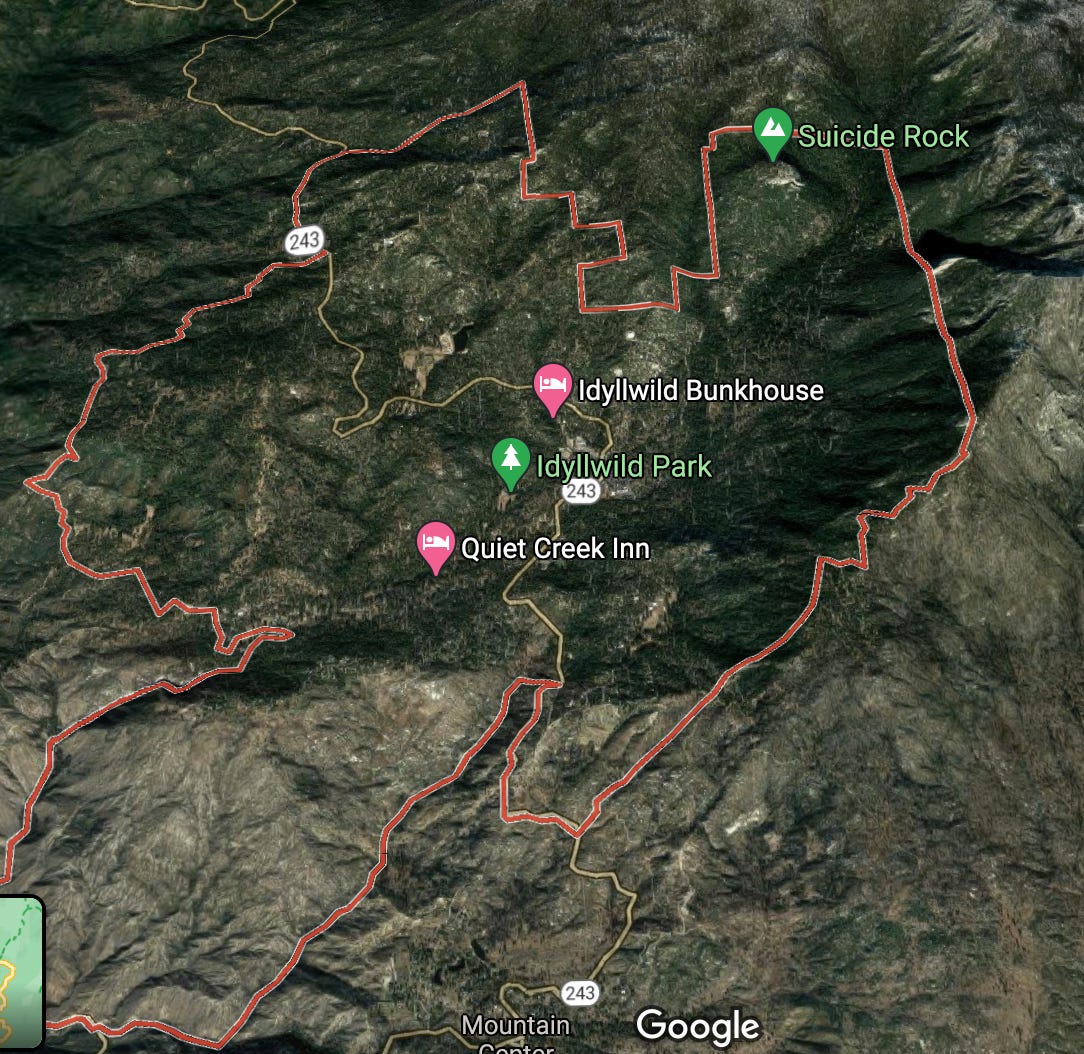

My husband and I spent the Labor Day weekend in Idyllwild, California, a mountain town a couple hours from Los Angeles. The landscape is like the Sierras, huge boulders from which pines grow, and thin trickles of creek that host mountain strawberries and fuschias. We hiked each morning, waking up at first light to reach a peak by sunrise, saying hello to masked and unmasked strangers on sandy trails.

What struck me, besides the beautiful landscape, was the small-townness of it all. The population is about 3,000. Log cabins and faux-chalets nestle among cedars, pines, and granite cliffs. The little town square is mostly ice cream parlors, coffee shops and tourist boutiques selling moccasins, hats, and “Keep Idy Wild” t-shirts.The local movie theater is closed for the quarantine and has given up the ghost; an entrepreneurial visitor can buy it for under $150,000. Restaurants close at 8pm on a Saturday. And the mayor is an adorable golden retriever named Max.

Mayor Max overseeing his jurisdiction, courtesy of Getty Images

Small Town Stories

So what kind of town votes in a dog for a mayor?

Our AirBnB was full of the telltale signs of an artsy progressive--mid-century style furniture, Seventh Generation dishwashing liquid, Post-it note exhortations to conserve water and energy, Silent Spring on the bookshelf. In the town, there were shops selling home-made soaps and candles, vintage records, and an excellent coffee roastery run by a tattooed woman with with pig tails.

Black Mountain Coffee Roastery

Other areas were streaked with down home conservatism. On a residential stretch driving into town, a handwritten sign in the front yard of a little house advertised award-winning salsas and jams. We stopped and walked past a small sign with a gun on it, saying, “Never mind the dog, beware the owner.” An older white couple welcomed us enthusiastically. The wife showed us all the state fair ribbons of her prize-winning jams, dozens tacked neatly to felted boards. Her husband, proud of his wife’s culinary skills, bragged that her pumpkin bread was the favorite of Miss America 1942, who lived up the mountain. We bought jam made from manzanita berries, a local bush native to the area, and a salsa made from Hatch chilies.

“I’m sweating clean through this mask,” she said to us. “I can’t wait till all of this is over. I can’t wait till the election is over.” We agreed, but didn’t press her on what she meant. As we drove away with half a dozen jars of sweet and spice, I saw two flags waving from the flagpole--an American flag, and a Second Amendment flag.

We visited a sporting goods store in town. It carried mostly guns, and the walls were covered in flags: Army, Navy, Don’t Tread On Me. The proprietor recognized my husband’s face mask--a Filipino flag--and started chatting with us. “My Pinoy brother,” he called my husband, and started telling us more about the town, populated by many veterans and former law enforcement. He told us,”I’m not going to hang my Trump signs everywhere; I’m equal opportunity when it comes to business. There was a BLM protest in the town square, and I let everyone use my bathroom if they needed it.”

In spite of clear partisan differences, there were no BLM signs and only one Trump sign and one Biden-Harris sign, as if there were a tacit and fragile agreement to be quiet about the partisan divisions so visible in other parts of the country. There was a sense of a community held together by relationship, and not political identity.

Red, Blue, or Green

The New York Time’s data section, the Upshot, recently compared satellite mapping to voting maps. It found a correlation between greener areas--showing less density of buildings--with Republican voting, and greyer areas--showing the urban density of roads, buildings, and houses--as voting more Democratic. From a satellite image, Idyllwild looks solidly green, which would correlate more closely with right-wing voting patterns.

I did a little digging on the political make-up of the town; the whole county of Riverside, a massive block spanning the fertile valley to the west and ritzy Palm Springs and sparse desert to the east, skewed slightly blue in 2016. Since then in Idyllwild itself, about ⅔ of political donations went to the Democrats and ⅓ to Republicans.

Community Bonding and Bridging

There’s a concept in sociology about how we build connection. One way is through bonding, building deep connections with those like us, in our proximity, and over time, leading to strong ties. The other is through bridging, building thin connections with those different from us, often through sporadic interactions, leading to weak ties. Generally speaking, small towns thrive on bonding relationships, whereas cities thrive on bridging connections.

One way many of us can find common ground is making politics less divisive, driving common ground in spite of differences. And what drives more common ground than having a dog for a mayor?

As we run up to the US Presidential election in one of the most divisive eras in recent memory, I want to explore community through the lens of bonding and bridging, and understand how we as individuals and in companies might use these concepts to connect and build a better world. In the next few editions, I’ll be looking at online communities, memes and communications, and the erosion of trust. If you’re interested in reading all the goods, sign up for all access.

2020 has served as a breaking point for so many structures in leadership, health, justice, economy, and equality. I explore how individuals and companies can find lessons out of this year’s challenges to create a better world. I’d love to hear what you think.