Warhol Owns Pop and Other Brand Truths

What Brands Can Learn about Distinctiveness from the Art World

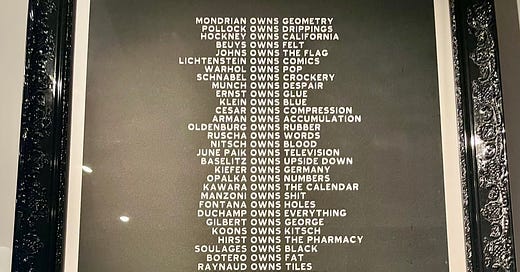

Almost a decade ago, a friend and I escaped SXSW early to go to Marfa, the tiny town in the middle of West Texas that’s become a haven for artists and creatives. We biked through the streets and stumbled upon a book and art store, where she found this print of Art History by Vuk Vidor and immediately picked it up. Ten years later, upon visiting her in Austin, I found it had a prominent place in her home, with a dramatic frame, on her wall.

This print is captivating because it boils down a series of famous and semi-famous 20th-century artists to one simple word.

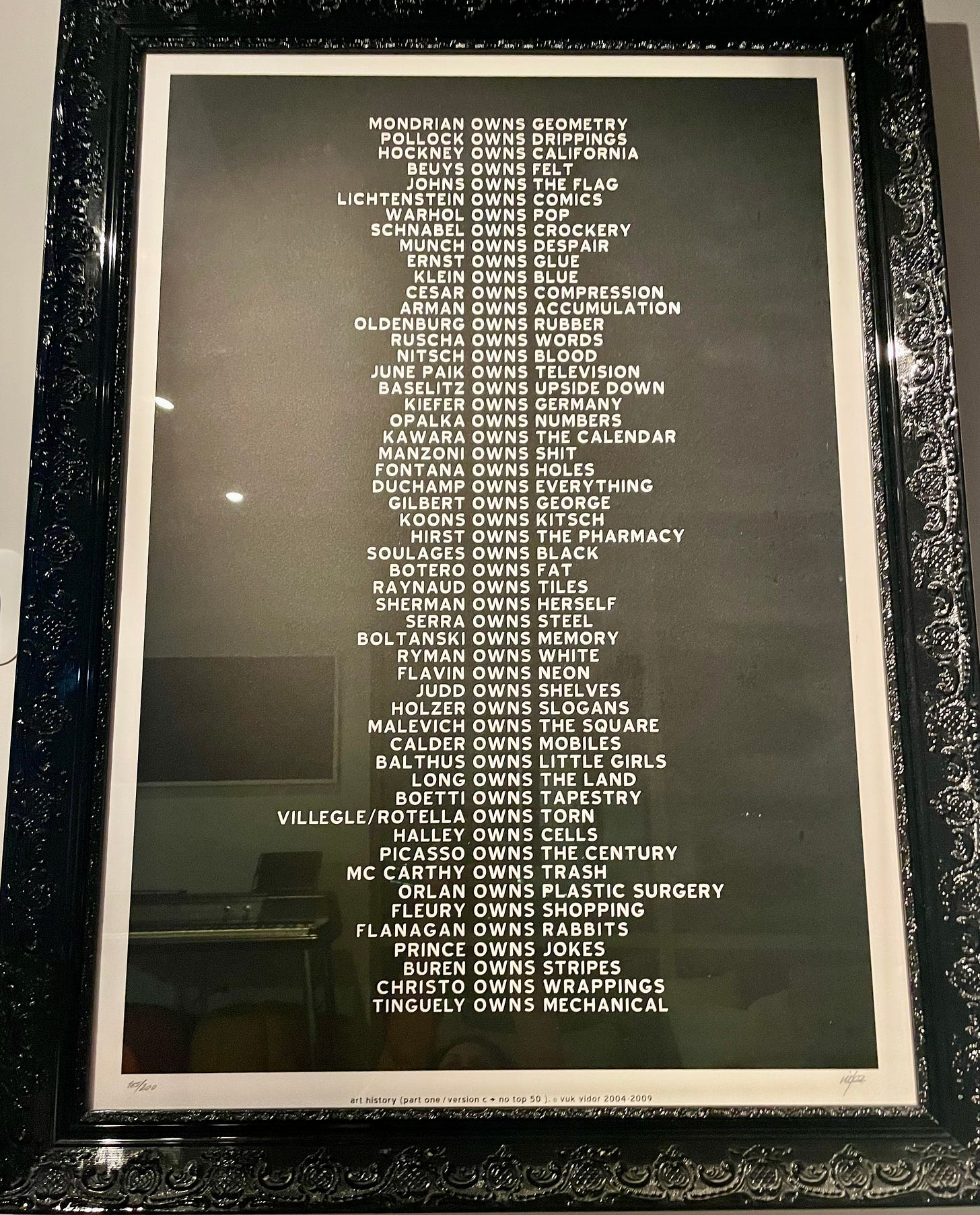

Holzer owns slogans.

June Paik owns televisions,

Christo owns wrappings.

Kawara owns calendars.

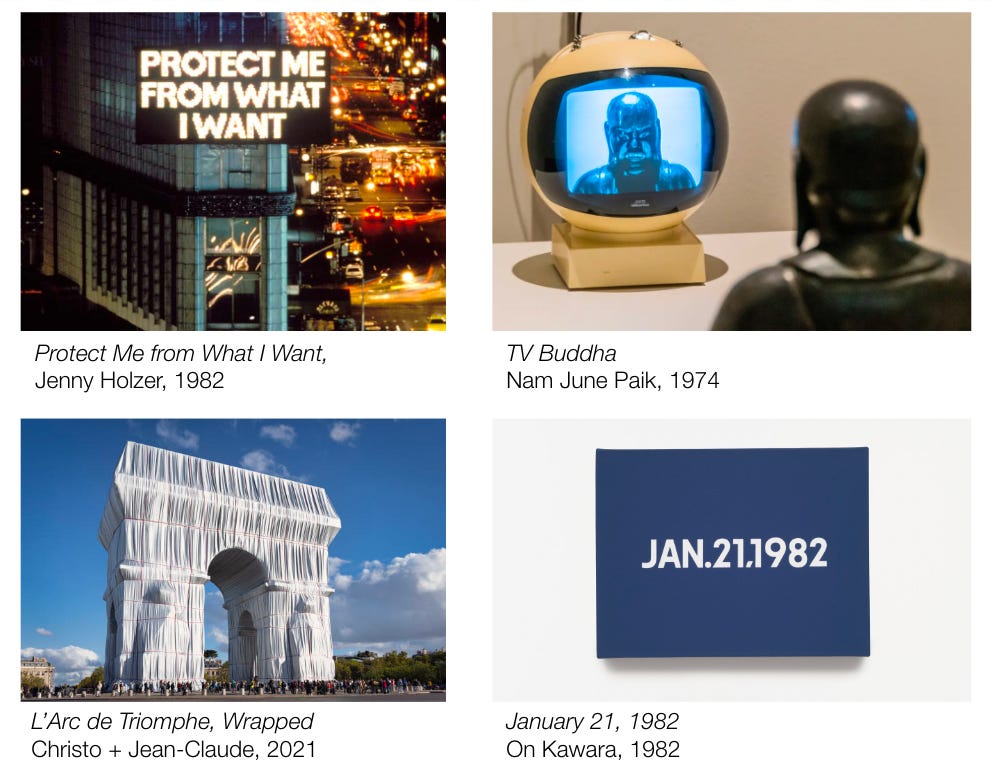

For anyone who’s aware of these artists, there are little winks. Duchamp owns everything, an ode to the man who started the Dada movement in the early 1900s and thereby radically changed art forever. Gilbert own George, a nod to the artist duo Gilbert + George.

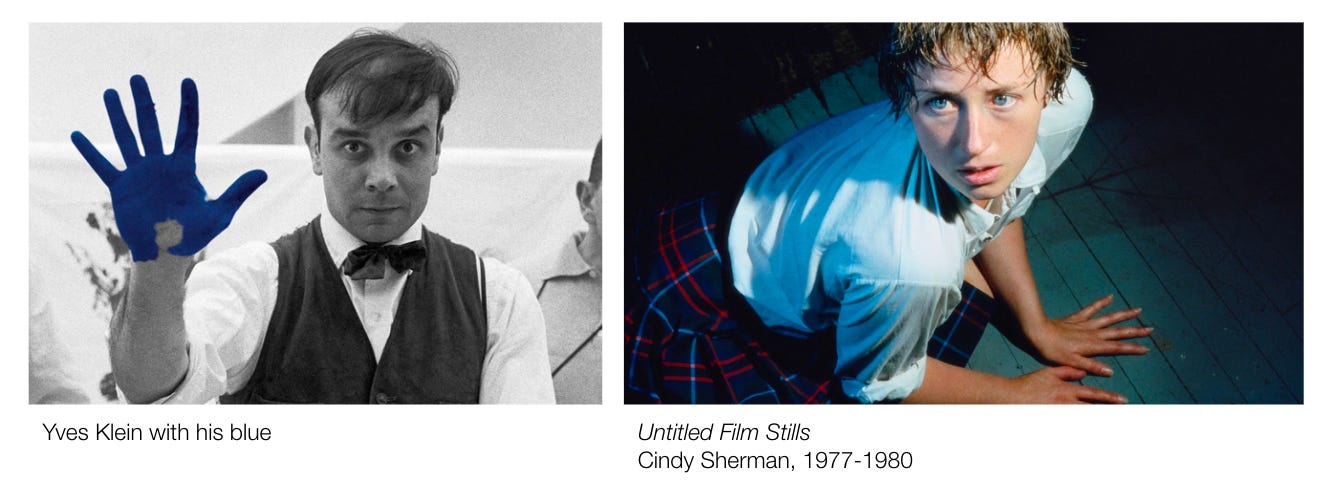

What I love about this poster is that it is so dead simple. In the art world, you may be able to quickly reverse engineer these hints. Some are a specific style or color—that artist that does blue will immediately be Yves Klein. That artist who obsessively documents herself is Cindy Sherman, taking up the practice decades before selfie became a word.

Successful artists have figured out what many brands still struggle with, namely being incredibly single-minded in what you’re known for. They recognize that once you stake a claim to a medium, message, or idea, it’s hard for others to play in that space without being considered derivative—one of the most debilitating judgments of any artist.

Brands, too, want this single-minded memorability, an association so crystal clear that it’s indelibly imprinted in our minds. Which brand is red? Coke. Why is everything on the planet turning pink right now? Barbie. What’s the swoosh, and Just Do it? Nike. The most iconic brands have the creative discipline and singular focus of an artist determined to break the mold and break into the world.

This distinction can be an aesthetic, lifestyle, or asset that feels unique from competing brands; it drives memorability, connection, and most importantly, the feeling that people have about that brand.

But you don’t get to the top with just dogged commitment to one thing. You need to get attention, and break through in a competitive, non-rational world of aesthetics, concepts, and existing relationships. Then you need to survive the thirst for novelty to establish yourself--both scratching the itch of expectation and constantly surprising.

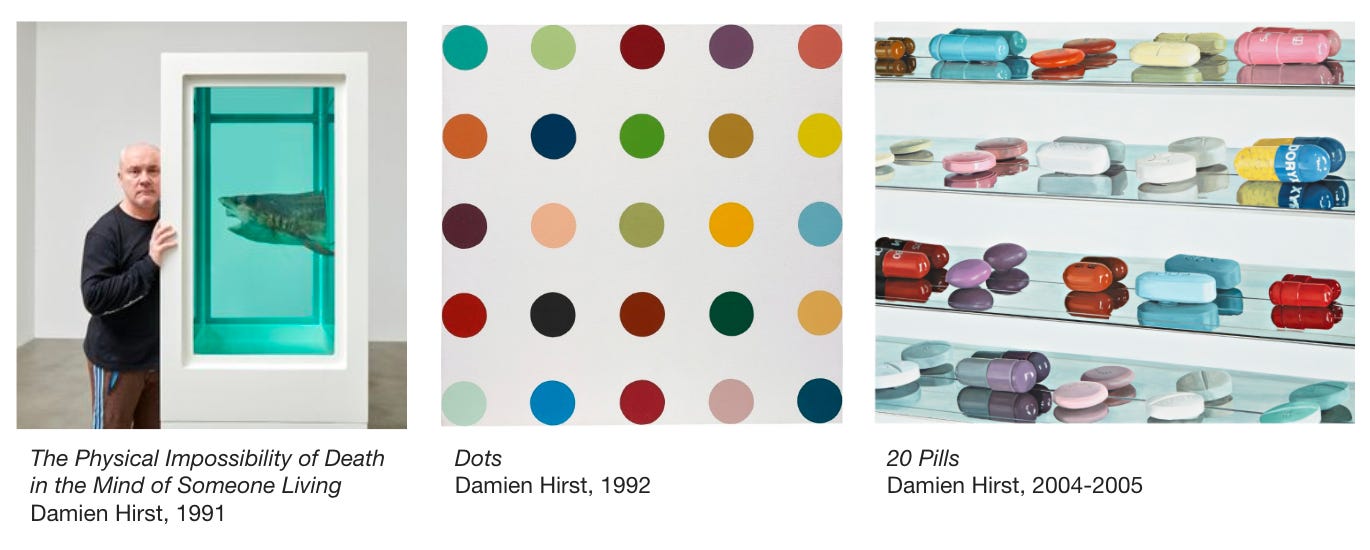

Damien Hirst, one of the most prolific and commercial artists of our time, knows this well, and trades off between producing repeated work that confirms our expectations, and pushing into new territories. He doesn’t only own “The Pharmacy,” as the print states, but has gone from “owning” taxidermied creatures to “owning” dots and on to several other iconic Hirst styles. This tension between the tried-and-true and the new has been very successful for Hirst; he’s worth $700 million.

In the hyper-competitive art market, there is no core differentiation; each work is made by a human seeking to tell their story and catch the attention of the world. It’s not the oil paint or any of the material that makes a difference (although, in some cases, a unique material does become distinctive to the artist, like Josef Beuys and his felt); it’s the unique expression and visual or experiential language that speaks to us, and thereby creates value. Brands seeking to create value above and beyond their core product differentiation would do well to learn from these artists.

You’ve just read Framing, a regular newsletter about what’s good culture, marketing, and business by Anita Schillhorn van Veen.

I’m Director of Strategy at McKinney, on the advisory board of Ladies Who Strategize, and a writer over at my other favorite Substack Why Is This Interesting.

If you haven’t yet subscribed, please consider being a paid or free subscriber.