Scarcity in the Time of Coronavirus

How the Principle of Scarcity Caught Up with a Culture Built on Abundance

The Quarantine Series

This is one of a series of articles about the lessons we can learn as individuals and companies as we move through times of disaster, to help us shape a better world moving forward. Read more & sign up for the newsletter here.

I park in the grocery store lot on a sunny day. It's early, so the lot is sparsely populated; on Saturdays people sleep in, lazy from a week of Zoom fatigue, or drawn to the sun after too many days indoors. I armor myself, mask first, then exit the car, then gloves, trying to minimize my gloves' contact with surfaces in the cocoon of my vehicle.

When I enter the store, The first thing I see is the empty toilet paper shelf. Two months into quarantine and it is still a barren stretch. Everywhere else is abundance; a locked glass wall of expensive champagnes, an end display full of kombuchas and cold brews, an overflow of freshly baked breads. Even with the news of meat shortages, the open fridges and the butcher windows are full of fresh cuts.

A lonely packet of ramen on an empty shelf.

And yet, seeing the empty shelf, a panic sets in. My mind shifts from the rationally planned list of groceries to a thrumming undercurrent of fear that it will all run out.

Living with Abundance.

Although I grew up in the country, I'm a city girl at heart. I spent my formative years in cities: DC, Philadelphia, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, New York. In each of these cities, the calculus of food-shopping is short-term. What do I need tonight?

In Amsterdam, my apartment was above the Albert Cuyp, a street market open six days a week. I woke up to the clattering of market stalls being erected and hawkers starting their day. The fishmonger started his mornings singing at the top of his lungs, his voice raspy from calling out prices and wares. The cheesemongers gossiped loudly, joyfully shit-talking each other, the weather, the news. The smell of bread baked before dawn and freshly made stroopwafels danced through my window in the summers. I lived short-term; I decided what to eat that day when I strolled past blocks and blocks of vegetables, meats, and cheeses.

The bustling abundance of the Albert Cuyp Markt, courtesy AmsterdamTourist.Info

In Brooklyn, I lived a half-block from a 24/7 market, bigger than a bodega, smaller than a supermarket, owned by Koreans and run by Nepali and Bhutanese. I got to know the cashiers; I saw them sometimes two or three times a day. Whenever I had an urge or needed a missing ingredient, it was a two-minute walk away.

This has always been my approach to food. When I want it, it's there. Stocking up felt superfluous in tiny city apartments. Carrying more groceries than I needed on a bike, in the subway, or on foot was tedious and unnecessary.

Now I live in Los Angeles, where I have a car trunk to fill and a kitchen with actual elbow room, but buying more than I needed still felt silly.

Perceived Scarcity in a Pandemic.

These days, a panic sets in the moment I step into a grocery store. A gnawing sense of fear that I will not have enough. That supplies will run low as a disease upends delicate balance of workers, delivery people, and distribution sites at every step of the supply chain. My shoulders tense, my mind goes blank, and I can barely keep two items from my shopping list in my mind at once. I fill my cart, almost blindly, like a kneejerk reaction to the fear. Beans, ice cream, potato chips, wine, frozen shrimp, gluten-free bread. A small voice asks me to look at the list, to stay focused, to think of our fridge, already so full. But the masked me doesn't listen.

I'm not alone in this. Early in the lock down, empty shelves of noodles, beans, and other dry goods accompanied the empty shelves of toilet paper and cleaning supplies. Finding a sack of flour felt like an achievement unlocked, as coveted as a Nike sneaker drop. There are no more express check-out for the people picking up milk or wine on their way somewhere. It's all carts, stacked high with goods.

We're all hard-wired to hoard when under stress. Neuroscientist Stephanie Peterson studies hoarding and notes that stockpiling is a way that humans and animals feel safer in the face of anxiety. Perceived scarcity has a profound effect on our physical and psychological being. Research shows that living with scarcity impedes our cognition. Psychologist Eldar Shafir has conducted research on scarcity and cognitive ability, and he notes:

There's a very large proportion of Americans who are concerned and struggling financially and therefore possibly lacking in bandwidth. Each time new issues raise their ugly heads, we lose cognitive abilities...People are walking around so concerned with one element of their lives that they don't have room for things on the periphery.

At this moment, there are few actual shortages; empty shelves are driven by overburdening a supply chain that's optimized for regular purchase patterns, as detailed by Helen Lewis in the Atlantic. She questions the doctrine of efficiency that has made our consumer goods delivery just-in-time to avoid the overhead of warehousing and waste, and that has also made our hospital bed amount tailored to have little overage for dangerous times like these.

Scarcity is no longer a marketing strategy.

Scarcity is one of the levers that companies have pulled to drive up interest. The scarcity principle—limited time deals, limited amount, buy before it runs out—is a tried and true marketing tactic.

Black Friday is the epitome of the scarcity strategy: one day, limited amounts, door-buster deals. The mayhem that ensues is a cultural ritual. For some it meant camping in front of the stores at 5 am, and for others it meant tsking at the evening news showing a video of two dads at war over a flat-screen.

Supreme has built its brand on scarcity, with exclusive sneaker drops driving queues of hype beasts to wait in line and fueling a powerful secondary market for laymen to wheel and deal on streetwear.

Is it the ‘rona or is it Supreme? Courtesy of the NYTimes

Events are by definition scarcity-driven, limited by number of seats and geographic location. Fear of Missing Out is built on the scarcity of time.

I’ve never been a fan of scarcity tactics; they work because they tap into an existential fear that clouds our better selves. The amount of stress we all carry because of living through a pandemic, assessing threat and fearing scarcity, can have long-term affects on our cognitive ability and on our mental state. Mental health experts predict that some will experience PTSD from the prolonged trauma of the pandemic. Rather than add to the sense of scarcity, marketers can help to craft a sense of safety.

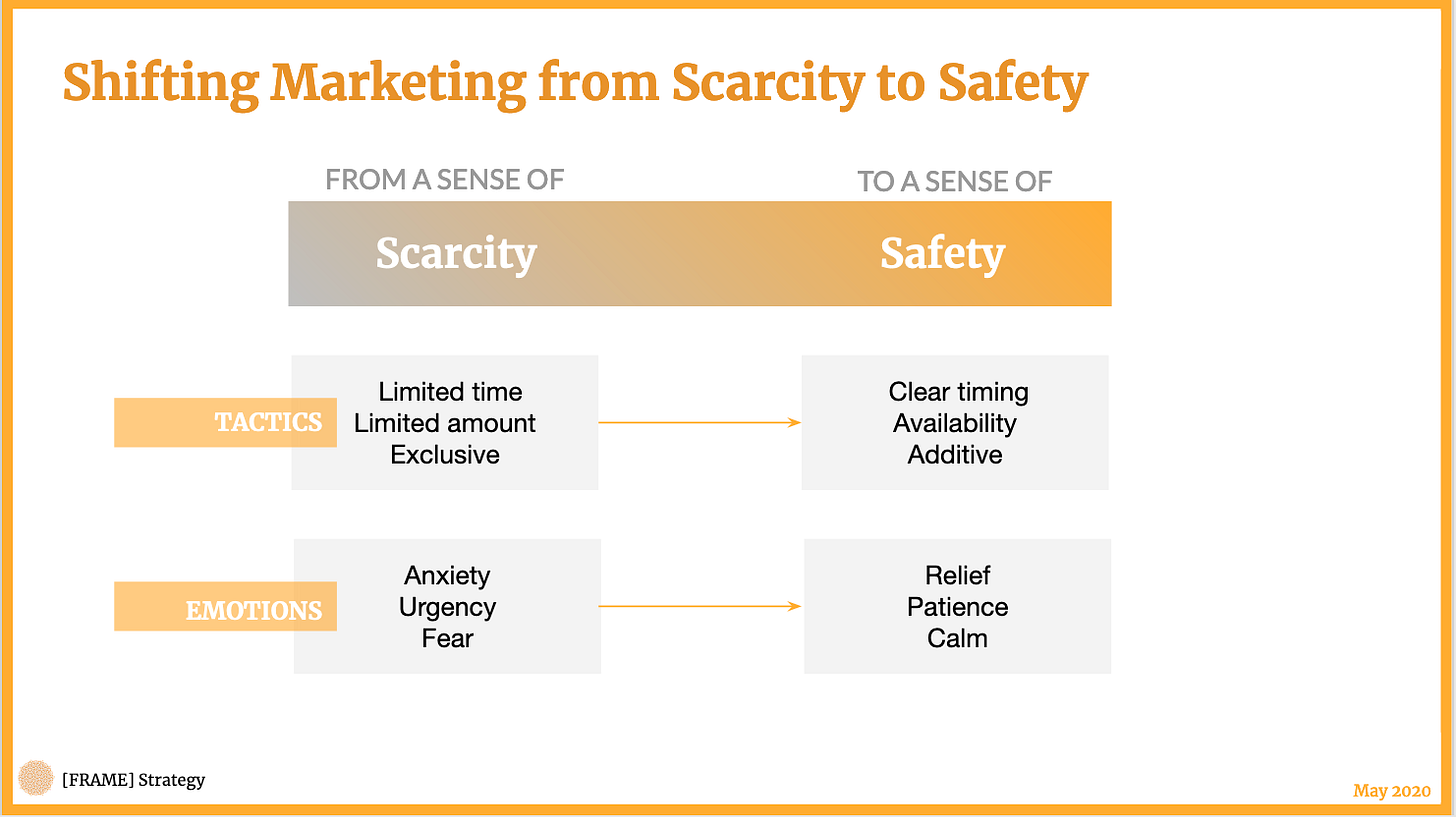

A few thoughts on shifting communications from scarcity to safety.

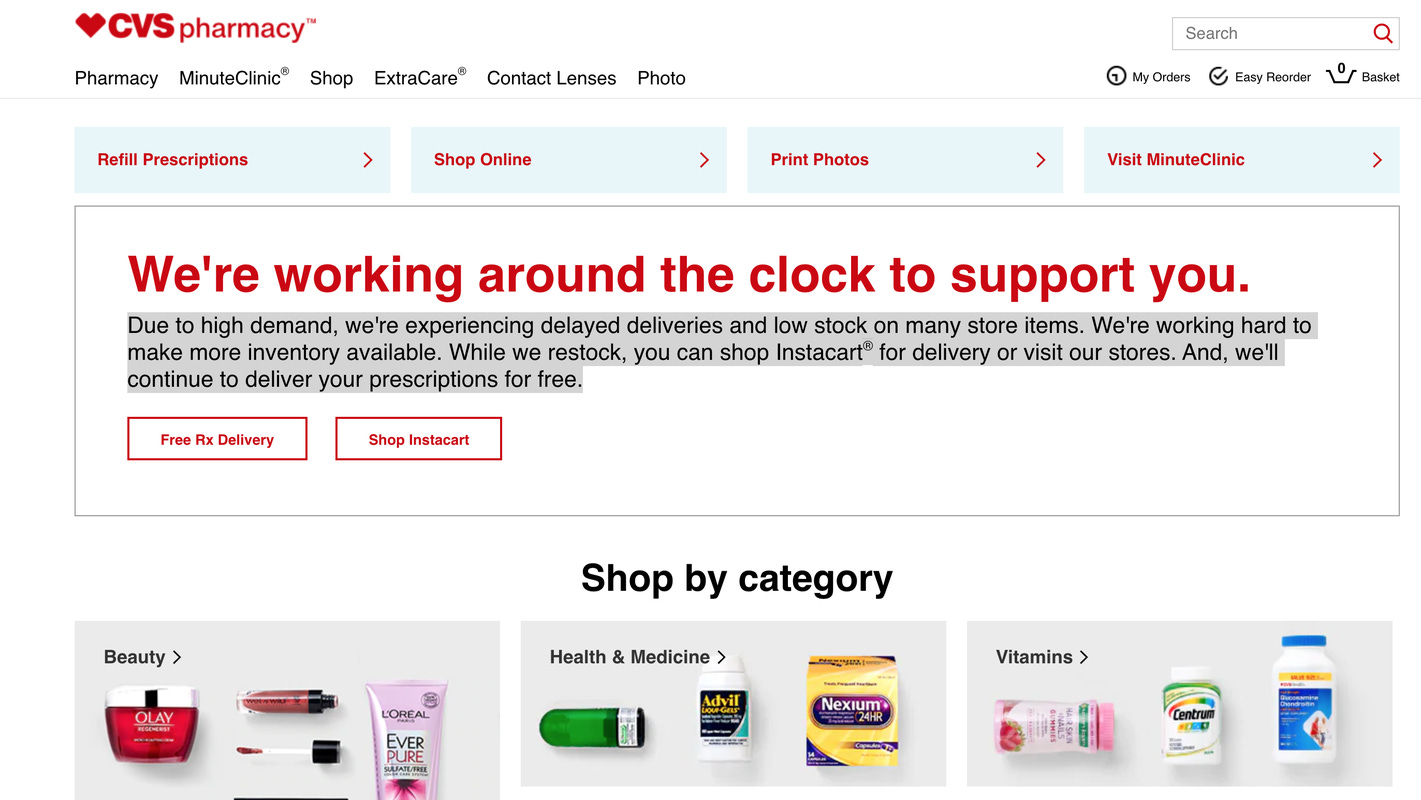

Limited time / Limted amount to Clear timing / availability

Hoarding is driven by a fear of not having enough. In the moment, whether the shortage comes from supply chain or from excess demand does not matter. What matters is that the consumer can feel some certainty about their being enough tomorrow. Communicating clear timing and availability can assuage fears. We saw plenty of these COVID banners pop up on websites, and whether you believe the message or not, conveying some certainty and effort can go far to disrupt the fear cycle.

Exclusive to Additive

Rather than driving exclusivity, this is a moment to be inclusive, and even better, to be additive.

In Denmark, Noma, the world’s best restaurant and one of the most coveted reservations, opened as a burger bar. As described in Esquire:

This is how Redzepi decided to respond to the global calamity: He wanted to make everyone feel welcome. Opening a wine bar alone would not have done that, because it would have been perceived as catering to its normal crowd. So he settled on a burger, “because it’s the thing that everyone loves.” A nomaburger, a dish for all seasons, an inclusive gesture of solidarity towards fellow Copenhageners by an exclusive restaurant that was alien to most of them.

Other initiatives are additive; FEW for All in LA sends a pound of pasta to a food bank and to out-of-work hospitality workers for each home-delivered meal.

Gestures like the above help alleviate the fear and anxiety caused by scarcity, if even for a moment. It’s not the time to tap into tried, true and terrible marketing tactics like scarcity, but to create a sense of safety and relief, to remind people of patience, to calm the inner voice that drives hoarding and fear-mongering.

As the esteemed chef Rene Redzepi told Esquire: “The most important thing right now is that we remember to take care of people, open the doors, smile at each other, get the positivity going, get the anxiety shaken off, you know, get a new era going.”

Thank you for reading. Next up: Poetry in the Time of Coronavirus. Read more & sign up for the newsletter here.