The Crisis Series. A month ago I began to write about what lessons individuals and companies can learn from quarantine to build a stronger post-pandemic world. In the past week, quarantine has given way to protest. I stand with the protesters, the organizers, the believers who see this moment as part of Martin Luther King, Jr’s long arc towards justice. I’ll pause on sharing frameworks for business practice while we collectively and painfully put our efforts towards a more just society in America.

In January 2017, I gathered a motley crew of women and men in Brooklyn. White, of South Asian and East Asian descent, Latinx, black, we organized rides, set up our Signal apps, and drove down to Washington, DC to participate in the first Women’s March. There were so many women crowding the National Mall that we couldn’t even march; the entire protest route was wall to wall people. Behind me two older white women tutted about how poorly organized the protest was, and how they were here to march, not stand around, a response that today would be filed under "Karen."

My friends and I stayed close, held hands, and reveled in the solidarity of women against the freshly inaugurated President, symbol and enacter of white patriarchal entitlement. The signs were clever indictments of the President, the patriarchy, and a hodgepodge of progressive issues. It was a jubilant outpouring of anger, solidarity, and pink knitwear.

And then.

I started counting the faces of Asian women, one of the races I identify with. In a sea of faces, there were a sporadic few, always with a group of white friends. I began looking for other races represented. In a city that’s 49% black, I saw barely any black people. I glanced at a Japanese American friend of mine, and knew what she was thinking. This brilliant sea of women fighting against the patriarchy was almost entirely white.

As the march dissipated, the police stood idly by without riot gear, directing women to the best routes to the metro. We went home and witnessed the ripple of marches around the world on TV and social media. Nothing changed.

Today’s Protests.

Spike Lee made Do The Right Thing in 1989, about an unarmed black man choked to death by the police, sparking protest and rage. In the 30 years since that film came out, the cycle of death and demonstration has only increased. But he notes this set of protests are different in their diversity, and that may be the key to change.

I’ve been very encouraged by the diversity of the protesters. I haven’t seen this diverse protests since when I was a kid…That is the hope of this country, this diverse, younger generation of Americans who don’t want to perpetuate the same shit that their parents and grandparents and great-grandparents got caught up in.

Although many protests have been peaceful, the images that have burned through the media are not. Police in riot gear, attacking protestors. Police taking a knee with protesters. Broken and boarded up windows in tony neighborhoods. Tanks in our streets. People chased into their homes. Daytime curfews. Dystopian levels of policing.

The policing and protests around the Lincoln Memorial, the memorial for the leader who ended slavery in a civil war. Image via NBC.

Safety is a privilege unevenly distributed. The privilege many of us rely on and work hard to get and maintain can dissolve in a heartbeat. The police and the Presidency are demonstrating to the nation that they do not care for black lives, nor for anyone who wants to protect black lives. It has woken many non-black people up to the fear that black people live with every damn day, and has forced us to reevaluate our relationship to race, our complicity in white supremacy, and the privileges we take for granted. Keisha Lance Bottoms, the mayor of Atlanta, sums it up in her New York Times article about power, privilege, and race, "The Police Report to Me, But I Knew I Couldn't Protect My Son."

The harsh reality is that if we examine the historical conditions of living while black in America, then we’ll realize that there has never been a day when it was truly safe for black boys to be out, to be free, to just be.

Safety in the Pandemic.

For the last three months in the pandemic, the world has been obsessed with safety from a disease. We lived under ‘safer at home’ orders to protect ourselves and our community. Safety gear like masks and gloves have flown off the shelves. ‘Stay safe’ has supplanted ‘good-bye.’ We’ve settled into our uneasy, frustrating, pants-free safety to engage in docile, domestic activity till it’s ok to emerge.

But safety takes on a different dimension when, even in a pandemic, a black person cannot be safe in her home, on a jog, or at a store. When the systemic racism in the health care system means black people die of COVID-19 at three times the rate of white people. When the authorities would rather unleash police violence on its citizens than prosecute four officers.

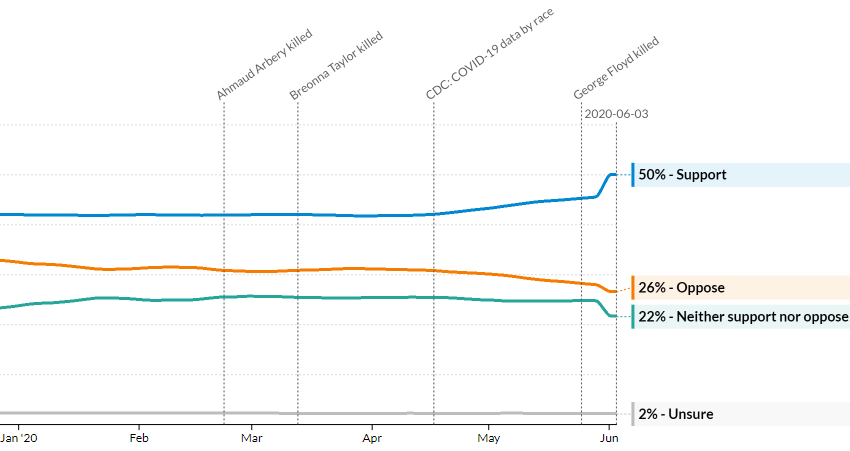

We've whipsawed between two versions of safety: 1. Being at home, protecting each other by separating, wearing masks and gloves and checking from afar. 2. Safeguarding society in the street, standing closer to strangers than you've been in months to friends and loved ones. More and more people are choosing the second option over the first, as the stakes for our democracy grow higher every day. The support for the Black Lives Matter movement has increased daily, and just topped 50%.

Image & annotations via Seiji Carpenter

Safety does not equal comfort.

In doing research for this post, I came across this phrase in a post about safe space theory. Rooted in the 1960s and 1970s feminist and LGBTQ movements, the idea of safe spaces is to have a community committed to learning and activism, to share experiences with people in the same pond as you without having to translate for men, or straight people, or people of a different race. It has found its home in education, and it reverberates in the idea of ‘psychological safety’ that has taken off in the workplace since Google named it the number one factor in building teams. In safe spaces, people are able to make mistakes, be honest, and sit in discomfort in order to grow.

To save our communities from the pandemic, we’ve all made uncomfortable sacrifices as a society. Small businesses have sacrificed income, communities have sacrificed social contact, and individuals have sacrificed so so much. We’ve stumbled through it as we’ve learned what works and what doesn’t work, wondering if we’re doing it right and course-correcting when we do it wrong. To be safe is not to be comfortable; it’s to confront a truth and take radical, long-term action to change it.

Like the commitment to end the pandemic, the commitment to end racism is not comfortable. It takes each and every one of us to confront how we participate in a white supremacist culture, as individuals and as institutions.

Most material on being an ally in this movement is shaped around whiteness, since we all swim in the same sea of white supremacy. Yet there are plenty of useful tools within white allyship material for people of all backgrounds. If like me, you're non-white , you'll find these material to both reflect and challenge your experience.

If you’re not American, you can’t tsk tsk that this is an American problem, because you’re also part of a world long shaped by colonialism and racism. In my little intersection of cultures, I read racist posts in Bahasa Indonesia that side with Trump’s authoritarianism, and posts in Dutch that lament the end of America without examining the Netherlands’ dark contribution to the slave trade and deep-seated racism.

No matter who we are or where we are, it's our jobs to understand that the world we live in has been shaped by centuries of slavery, colonialism, and other centuries-old historical power structures that elevate whiteness above all.

So what do we do?

This question has reverberated across the internet, in my social channels and personal feeds. What those of us who are not black do is we enter a space of discomfort, to sacrifice perfection in order to change ourselves and our society for the better. For those who are black, you’ve done so much to get our attention, to fight this, to live through this every day. The mantle of discomfort must be shared to lighten the load.

If I were to augment the stacks of reading lists, it would be with a global eye. I’ve built a list on dismantling colonial legacies on Bookshop.org. Franz Fanon, Benedict Anderson, and Edward Said have all written eloquently about the constructs of race, colonialism, and power. Or with a personal eye. Audre Lorde is the poet laureate of the political as personal, and over the last few days I’ve frequently read her essay “The Transformation of Language into Action,” thanks to GirlTrek’s Black History Bootcamp.

If I were to tell you what’s consistently woken me up to the black experience in America, it’s music. Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet was my first rap album as a kid, and it taught me more than my middle school history and civics courses. Beyonce’s Formation is as rich a text as a Toni Morrison novel. Kendrick Lamar’s Blacker the Berry feels like it was written like yesterday morning. If you didn’t internalize the message of Childish Gambino’s This Is America when it was a hit two years ago, it’s time now.

If I were to tell you consuming media is just a starting point, I would say take action locally. The police are run locally. Mayors and City Councils make policies that impact racial disparities in your community. And this is the moment—Los Angeles’s community police meeting was such an explosive moment that it was picked up by the British tabloid the Daily Mail. The meeting contributed to the Mayor slashing over $100 million in police funding from the proposed budget, a first step in a movement fueled by the coalition of organizations supporting the People’s Budget, to change how the City prioritizes its funding. Push yourself to research what’s possible, and then do an action that makes you uncomfortable. Make a phone call. Fund an initiative. Go into the street.

I’m of the opinion that we may witness the undoing of the American democratic experience if we don’t act now. If we cannot protect the safety of young black men, none of us are safe.

One note as I re-read this essay; in my first version, I made assumptions about my readership. In my "so what do we do" section, the "we" I was speaking to was not black. I woke up this morning with a holy-shit moment, recognizing that in doing that, I'm perpetuating the erasure of blackness. I've revised this section to clarify that. It is the duty of people who are not black to take on the work of getting deeply uncomfortably empathetic with what black people have gone through for over 400 years, and my recommendations here are targeted to this end goal.